By targeting Kashmiri students, did fanatic groups not undermine India’s message? And by not acting firmly against them, did Modi send the right message to Kashmir and Kashmiris about their future with India?

“The Kashmir conflict will be resolved within the parameters of insaniyat (humanity),Kashmiriyat (composite secular, eclectic Kashmiri culture) and jamhooriyat(democracy),” were the words of our late prime minister A.B. Vajpayee.

While growing up in Kashmir during the early 2000s (when NDA-I was in power), one could see a deepening of jamhooriyat in the backdrop of the humane policy (insaniyat) of the Central government. Vajpayee rightly gauged that after more than a decade of armed conflict, Kashmiris wanted peace. This formed the basis of his Kashmir policy, a positive impact of which was evident in the sharp decline in the number youth picking up arms. The number of terrorist attacks saw an equally sharp decline.

Vajpayee’s acknowledgement of the suffering of Kashmiris helped to bridge the emotional disconnect between ordinary Kashmiris and New Delhi. A significant development in that context was the gradual withdrawal of the army from civilian areas.

Some initiatives taken by the army and the Centre to mainstream the younger generation of Kashmiris had a visible impact. For instance, the all-India educational tours organised by the army contributed to a huge number of students moving to different states of India in search of better economic and educational opportunities.

Expectations spurned

While some of this momentum continued, New Delhi’s Kashmir policy became hostage to India-Pakistan relations and by the fag end of UPA-II, Kashmiris once again began to feel alienated and anxious. That is why a hesitant welcome was given to the Narendra Modi government from all sections of the political class in Kashmir. They hoped for a change in the status quo, along the lines of Vajpayee. Sadly, those expectations turned out to be wrong.

Modi’s muscular and overtly militaristic Kashmir policy acted as a catalyst for a new wave of homegrown militancy. The disproportionate use of pellet guns against protestors provoked a larger number of ordinary Kashmiris to take to the streets.

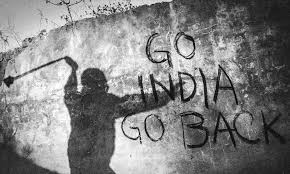

Media houses played an important role in supporting Modi’s aggressive Kashmir policy by their skewed representation of the ordinary Kashmiri as a perpetrator of violence rather than a victim. Masked Kashmiri youth pelting stones at security forces became the image the national media preferred to project.

As a result, an apparent ‘othering’ of Kashmiris became the norm; “stone-pelter” became synonymous with Kashmiri. Acts of violence against Kashmiris in some north Indian states after India-Pakistan cricket matches were ignored and normalised.

This policy happens to be in line with the approach that Ram Madhav of the BJP believes is necessary to mainstream the ‘misguided’ Kashmiri youth:

“The people of India must remember that when they say “Kashmir is ours”, that also means “every Kashmiri is ours”. If he is misguided, lead him; if he is mischievous, punish him; if he is treacherous, banish him. But instill India in him.”

The violence after Pulwama

It is in this context that one should see the targeting of Kashmiris after the Pulwama attack. The violence unleashed on Kashmiris for the mere reason that they belong to a particular region of the country is against the principles of jamhooriyat and insaniyat. These attacks were merely based on the image of a stone-wielding Kashmiri, both men and women, old and young, created over the last few years by the Indian media.

In the days after Pulwama, anyone could “punish” the Kashmiri by invoking nationalism. The presumption here was that every Kashmiri is either a terrorist or a supporter of terrorism. Some colleges in Dehradun were forced to rusticate Kashmiri students; employers were coerced into terminating the services of Kashmiri employees, and landlords were warned against keeping Kashmiri tenants.

The statement by the current governor of Meghalaya calling for a boycott of Kashmiris and Kashmiri products went unpunished. It is important to mention that it took more than a week and a notice from the Supreme Court of India for the prime minister to acknowledge the violence against Kashmiris in the aftermath of the Pulwama attack.

Deep sense of insecurity

Thugh they eventually subsided, these attacks have given rise to a deep sense of insecurity among Kashmiris. According to some reports, around 8,000 students have returned to the valley. These students are unlikely to go back to their colleges, particularly female students, unless there is action against the groups which targeted them. Most of these students were part of the PM’s special scholarship scheme for students from J&K.

The fact that these students are in the middle of their semester demands quick action on the part of the government to ensure that their academic year is not wasted. No steps to that effect have been taken till now, either by the Centre or by the governor of J&K.

By targeting Kashmiri students in this way, did fanatic groups not undermine India’s message? And by not acting quickly and firmly against them, did Modi and his party men send the right message to Kashmir and Kashmiris about their future with India?

One of the main arguments BJP leaders like Ram Madhav make in favour of abrogating Article 370 and Article 35A is to complete the assimilation and integration process of J&K with India. But is India ready for it?

Once Article 370 is repealed, where would Kashmiris go in case they are attacked in other parts of the country? Do these attacks not validate the apprehensions ordinary Kashmiris have about the demand to repeal Article 370? The process of mainstreaming and assimilation will not succeed unless Kashmiris feel equally safe outside Kashmir as they feel in Kashmir.

The trick is not to abrogate Article 370 but to make it irrelevant, and there is a big difference between the two.

Malik Altaf Hussain and Aejaz Ahmad Rather